pRESS

tHERE ARE OLD THINGS IN THIS FAMILY…

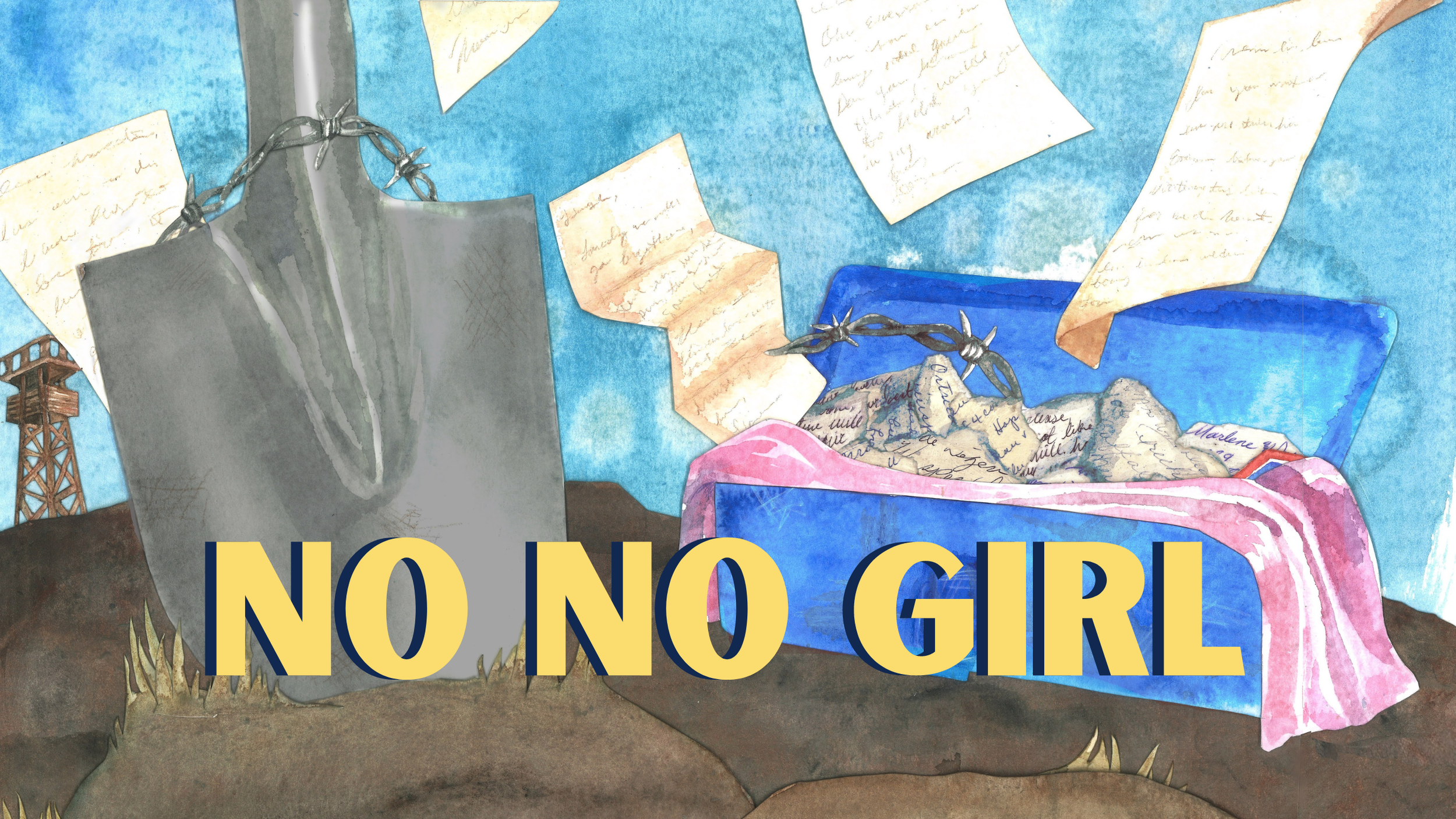

Japanese American National Museum premieres cancer-battling director’s film on pains of WWII incarceration camps

“Goodman, 30, developed the film with his own family in mind. His grandfather was among those incarcerated at the Rohwer Camp in Arkansas and later enlisted in the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat Team. NO NO GIRL, attempts to portray what it’s like to be “removed” from history.”

-NEXT SHARK

Exclusive: No No Girl Director Talks AAPI Film Produced During Cancer Battle

“Learning our own family history can be so important to shaping who we are. No No Girl is a new feature film that just premiered at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. Co-starring Oscar winner Chris Tashima, it's the second film by Paul Daisuke Goodman, a two-time cancer survivor. It's a small, independent film but has a strong heartwarming message about family and family history.”

— MOVIE WEB

A Triumph in Front of and Behind the Camera

“The impact of the wartime incarceration on Japanese Americans today is explored in “No No Girl,” written and directed by Paul Daisuke Goodman. The film was previewed at the Japanese American National Museum in August, followed by a week-long run at Laemmle’s Glendale theater; screenings at Orange County Buddhist Church, where Goodman is a member”

— rafu shimpo

“In “No No Girl,” Goodman tells that story with aplomb, weaving together many characters and elements, some quite heavy, yet lightened by the goofy, Laurel-and-Hardy-like interplay of cousins Kento and Alan. Their speculations about Bachan become even sillier when the poignant truths and heirlooms are finally revealed.”

Paul Goodman’s Reel Life Triumph

Trailer

Teaser

From the director

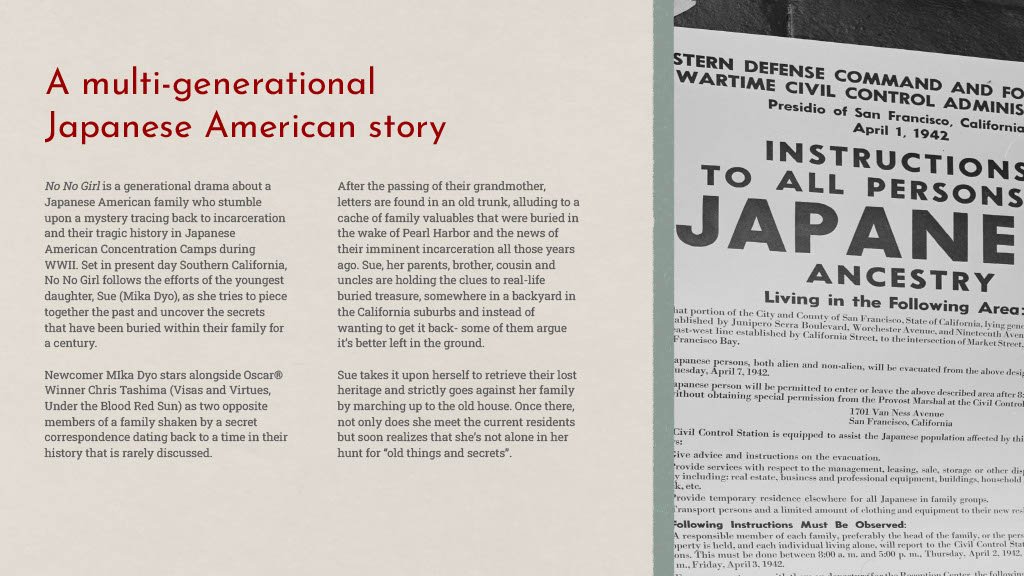

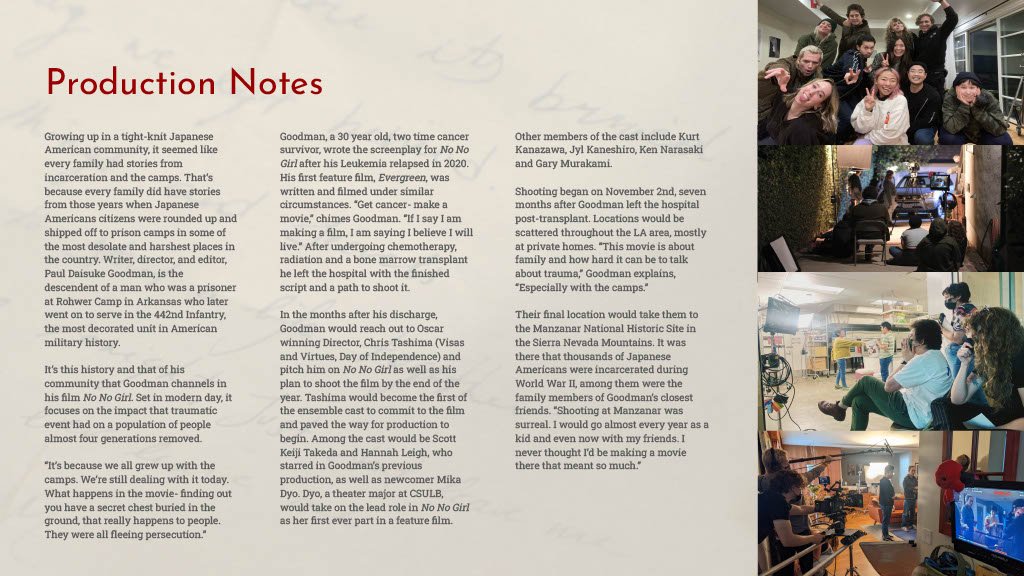

Who has heard of Manzanar? Or Rohwer or Tule Lake? No-No Boys and loyalty questionnaires and the American Concentration Camps? This is the history that I grew up with as a fourth generation Japanese American whose ancestors were evicted from their homes and put into concentration camps after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Many of the people who worked on this film and almost every Japanese American can trace their way back, one way or another, to a camp in some desolate corner of the country. No No Girl is just one of the stranger-than-fiction stories that have been so underrepresented in today’s narrative storytelling.

No No Girl addresses generational trauma and how even now, almost a century later, we are still dealing with the consequences of that unlawful decision. I grew up in a tight-knit Japanese American community and on the surface, like most trauma, no one would be able to tell that two generations ago we had everything taken away from us. Our characters in this film represent that perseverance but also the life-long secrets and shikata ga nai attitude that came from getting through impossible times. The events of this film may seem outside reality – a family discovering the existence of buried heirlooms in the backyard of a long evacuated suburban home – but in my community, it doesn't even scratch the surface of the strange and unbelievable folklore that gets passed along. With unbelievable circumstances come unbelievable people and choices one must make.

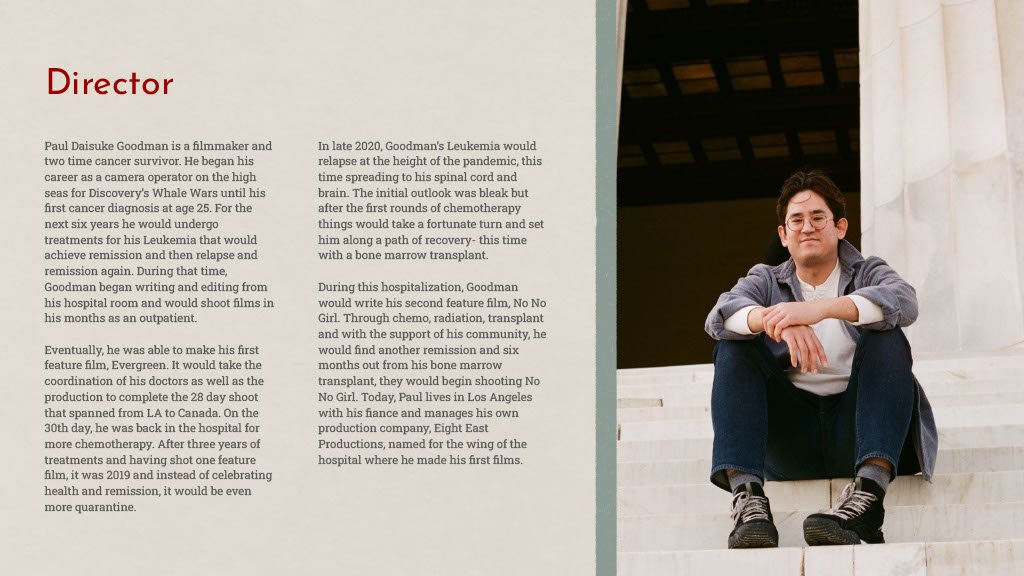

This film was made with an all Japanese American main cast and even behind the camera there is a huge representation of AAPI talent. I am so proud to have made this story with the community that it represents and to feel their collective support as we pushed forward through production. While I was writing the script in 2020, my cancer relapsed and I found myself in the hospital at the worst of the pandemic. Vaccines were not yet available and I needed a bone marrow transplant. It was some of the most painful and harrowing months of my life.

Many people who worked on this film are the very people responsible for my recovery and eventual remission. I finished the script right before I was discharged, barely able to walk after the radiation and chemo and bone marrow transplant. We would start shooting No No Girl six months later and it was this community and my family that made this film possible. It’s what made this story real.